Discursive Misdirection

AI is not intelligent and AI is not creative. But it is about labour.

We are tired PhD students who like to think and work together. While Nancy’s work is on tech, temporality, and cultural production; and Rutendo’s work is on feminist approaches to citizenship in the digital - we are both committed to material analyses of technology. This post is the first in a series of an unknown and incomplete number of posts.

Among the many conversations surrounding generative AI are conversations of creativity: can AI be creative? This is a jarring parallel discourse to AI and intelligence: is AI intelligent? They are iterations of a discourse where AI is agentic and spontaneous. The questions refer to an almost existential threat: AI is always potentially more intelligent, more creative than us.

AI is a threat, but not because it is potentially more intelligent or more creative.

AI is already a threat to labour and life as a result of the exploitative systems of consumption and production requiring massive amounts of precarious human labour and natural resources to train and run these systems. The conversations on the “creativity” of AI obscure the politics of AI systems.

In this post, we do not question whether AI could be a useful tool and whether it is effective or not effective at being creative or thinking. Rather, we interrogate these questions as redirection from material questions of resources and exploited labour. The formulation of sociotechnical issues as long-term existential questions discourage substantive reflection or action around power.

Within an AI creativity discourse, generative AI is raised as a question of the aesthetic quality of generated media, where the capacity for computational creativity must be recognised and explored in its own right. It obfuscates that generative AI is the result of the wholesale theft of creative labour and often suggests that workers should rethink themselves as creative ‘collaborators’ to technology, adapting their practices to accommodate this corporate appropriation. Further, the rumination of an AI intelligence gives these systems a sense of agency and autonomy that has been denied to many in histories (and presents) of race science and eugenics.

We make the case of the constitutive effects of this discourse.1

Whose AI is it Anyway?

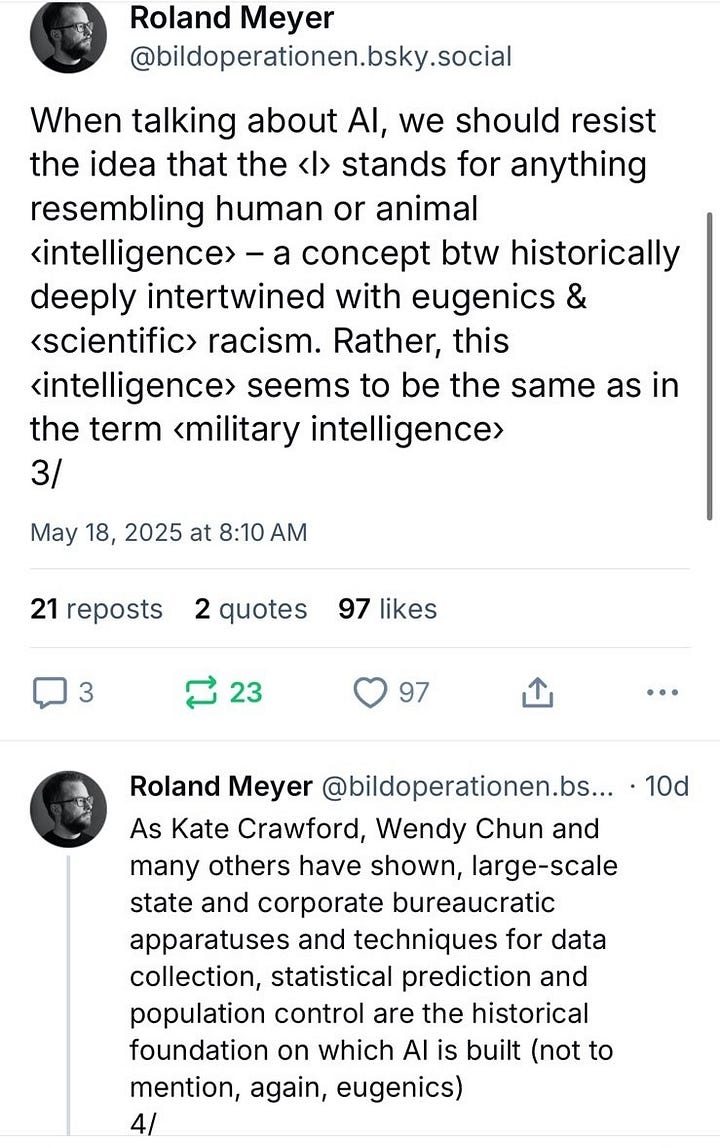

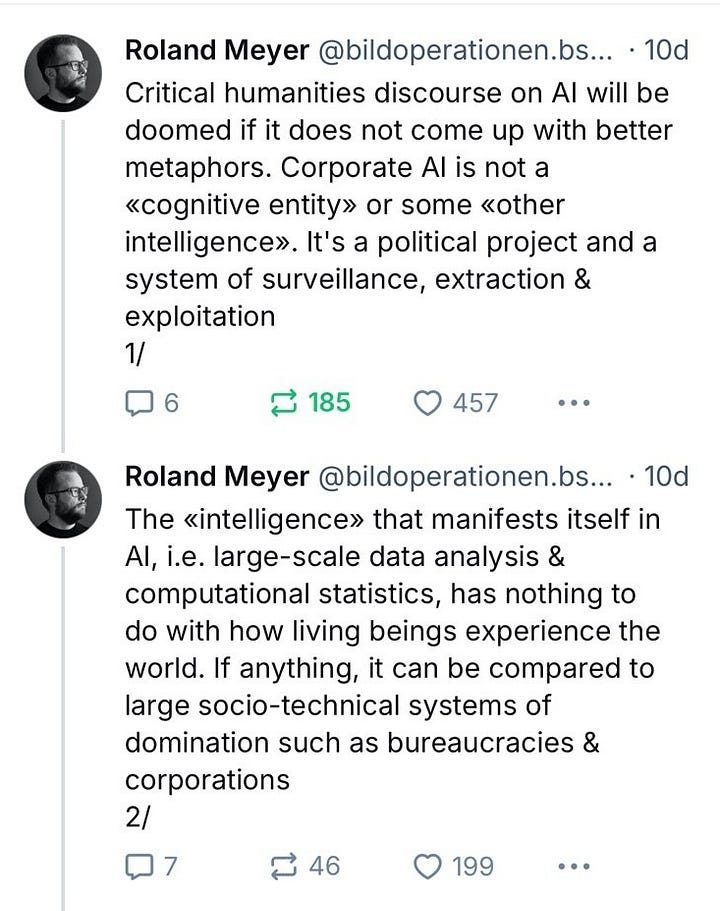

The Oxford English Dictionary online has 8 definitions of “intelligence” as a noun. A common thread in all these definitions is the concept of understanding, knowing, rationality, and comprehension – terms which immediately anthropomorphise AI. AI is not only anthropomorphised in how it is named, but how we speak of it in popular discourse. Is AI any good at choosing gifts?, Would you let AI plan your next holiday? But the idea that these technological systems of extraction and production resemble anything human are not only inaccurate but are highly insidious. While this conversation on the dangers of anthropomorphising AI is not new, it is most certainly urgent. Current scholarly interest in the potential of intelligence or creativity redirects our attention from questions of political economy and denies us a more measured conversation about the harm of AI, as scholar Roland Meyer identifies:

The history of the search for intelligence is steeped in murder, racism, sexism, xenophobia, ableism and, classism. Eugenics has always been about seeking to establish a superior race and/or class, arguing that certain groups of individuals just don’t have it. Narrow concepts of “intelligence” have been used to justify multiple forms of violence including slavery and settler colonialism. When an entire group of people is deemed unintelligent, it is to ascribe them as less than human and therefore deserving of that structural violence. That the very attribute that has been and continues to be denied to large communities of humanity, is now so easily attributed to a non-human system should not be seen as unintentional.

When eugenists argue(d) that individuals of certain races, classes, abilities etc. are not intelligent, it is/was not only to justify violence but to also control - to lay claim to being responsible for areas of life and lands inhabited by the now ‘othered’ people, communities, and lives. This similar framing is at the root of colonial and imperial ideologies such as manifest destiny - that other lives, if they are even deemed to exist, are less intelligent and thus responsibility over them falls on the more intelligent life form. By using the metaphor of intelligence for AI, the reverse becomes true.

Who then can be held responsible for something deemed intelligent?

It is not the corporations that are building and expanding data centres that require so much energy, pushing us further into the depths of a climate crisis. When the issue is mentioned, it is: AI has an environmental problem, AI’s climate impact goes beyond it’s emissions, or AI likely to increase energy use and accelerate climate misinformation. It is not the individuals who are making billions from this creation, because it is, afterall, intelligent.

By insisting that AI is intelligent we overshadow and ignore the corporations that create these systems and thus remove responsibility from the parties causing harm. We also ignore that people are beginning to rely on AI because certain systems2 - social, economic, and political - that are allowing this “boom” to occur have failed them already. It appears as though this proliferation of AI is a natural progression, a part of our social evolution, yet it is specific corporations, individuals, and institutions placing this “intelligent” system before us in every way possible. Calling it intelligent removes the actors in the discourse regarding AI, and with no actors there is no one responsible for the “harms that AI” can and does cause.

So who actually is intelligent and creative?

The cultural worker.

The cultural worker, whose field has been subject to funding cuts and commercialisation for decades is further refigured in terms of a ‘creativity’ we should assume generative AI has. Artists should use, collaborate, or differentiate themselves to AI. We already see a demand that we adapt our labour to generative AI into a discourse of ‘human workers, augmented with AI’ as one Deloitte report terms, tying together generative AI with gig work, a model of labour that is associated with a persistent race to the bottom in wages and labour protections. The report reads: “together AI and alternative work arrangements are creating an augmented workforce that challenges organizations to fundamentally reconsider how jobs are designed and how the workforce should adapt.” We cannot help notice that amongst the skills of the future are those that have been regularly feminized and therefore devalued in the past, in particular, the skill of empathy that has been so routinely decried as irrational, a soft skill.

So, what now?

Technological discourse has a way of moving on, despite response and contestation, and without recourse. We draw attention to an emerging Content Authenticity Initiative that has drawn together an exhaustive list of media actors, private companies, and non-profits pledging to use and endorse content credentials. It is a sociotechnical infrastructure of software and hardware that allows media and their authors to be verified as ‘real’. Paradoxically, the very same tech companies embroiled in the theft of creative material to train AI models are the same companies now looking to set the normative relations of trust in online media. There are very important reasons journalists or other media producers might not want to go through the authentication process, concerns over surveillance and protection of sources. The group acknowledges that a two-tiered media system might emerge from this initiative, but they iterate that it is not their intent. In the widespread and well-documented instances of harm from the tech sector, intent seems a strange choice of word – a company or initiative again, is not a human, how is intent being mobilized here to absolve companies of responsibility?

All the meanwhile, more and more AI ‘slop’ is being produced and reproduced online clogging up our platforms. The more slop that we are forcibly exposed to, the more we question and the less interested we become.

Michel Foucault, Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language (1969) (trans. AM Sheridan Smith, 1972), 135-140 and 49.

These systems, such as capitalism, are also often referred to in ways that remove the responsibility from any actors. We speak of “the market” as if it is a living and breathing thing and not a system of power with very specific actors within it.